The Kurdish Language

The Kurdish language is the fourth most-spoken language in the Middle East after Arabic, Turkish and Persian with approximately 40 to 45 million speakers. Yet this language is not unified and has never been standardised. Kurdish has many dialects, some of which are quite distinct from one another.

Kurdish belongs to the Indo-European language family and more precisely to the Indo-Iranian branch of this family. It is spoken by the Kurds, who populate a vast region called Kurdistan, currently divided between four states: southeastern Turkey, northwestern Iran, northern Iraq and northern Syria.

There are also pockets of Kurdish culture that have settled in other countries, due to displacement and deportation throughout history. Thus, there are Kurdish and Kurdish-speaking communities in the Caucasian countries, Central Asian countries, Russia, Lebanon and Israel.

A few million Kurds have also fled their countries in recent decades and exist in diasporic communities of varying size in numerous Western countries.

It is important to first examine the geographical distribution of the different dialects of Kurdish and their origins, before seeing if the speakers of these dialects can understand each other and finally we will analyse the policies of defence, development and standardisation of Kurdish.

Kurdish Dialects and their Geographical Distribution

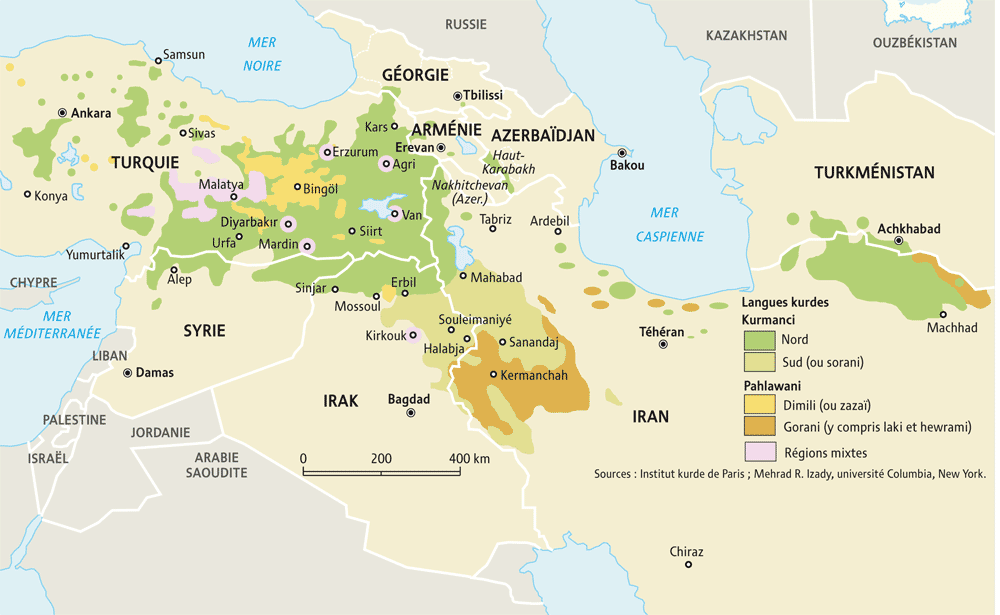

Kurdish is divided into four dialects, Kurmanji and Sorani, Gorani (including Laki and Hewrami) and Dimili (or Zazaki). Gorani and Dimili share common unique characteristics, which have been studied by researchers, despite the fact that the speakers of these two dialects are the most geographically distant among the Kurds.

Kurmanji is the only dialect spoken in the four parts of Kurdistan, since it is found in southern and eastern Turkey, northern Syria, northwestern Iran and northern Iraq, more precisely in the northern part of the Autonomous Region of Kurdistan, as well as in the major cities of Turkey such as Istanbul where there are an estimated 3 million Kurds. Sorani is spoken in the south of the Kurdistan Autonomous Region of Iraq as well as in western Iran. Gorani is spoken in the southern Kurdish regions of Iran and to a lesser extent Iraq, and Dimili is spoken in the north of the Kurdish regions of Turkey.

Map of the Kurdish dialects spoken in different areas. Credit: Kurdish Institute in Paris

It should be noted that these last two dialects are considered endangered varieties by UNESCO because they have few speakers and intergenerational transmission.

Due to changes in geo-political relations and cultural exchange, every language is subject to change over time. Kurdish is no different, with both its vocabulary and grammar shifting over time to adjust to the developments of the larger region.

A significant determinant for the evolution of the Kurdish dialects has been the geography of the area. The mountainous terrain has always made exchanges and communications difficult. So each sub-section of the regions has developed and kept specific characteristics.

Finally, the unification of languages is inherently political. The Kurds did not have the opportunity to found a state and bring out a common language, and the language was never unified like the European nation-states during this time, so only dialects were preserved.

Without unification, each dialect also developed somewhat under the constraint of the official languages of the modern states that emerged from the First World War, in which its speakers lived. For example, Sorani borrowed many words from Arabic or Persian, while the Kurds of Turkey (Kurmanji) borrowed words from the Turkish lexicon.

There are also grammatical differences between the different Kurdish dialects. For example, Kurmanji retains the grammatical gender (masculine-feminine) while Sorani does not. The Dimili also retains gender differentiation in its use of pronouns. Kurmanji has two types of pronouns, the nominative and in the indirect case, while Sorani has reduced this to a single group. There are also phonological differences between dialects.

But with all these differences, can the speakers of these dialects understand each other?

Communication between the Kurdish dialects

Until 30 or 40 years ago, inter-comprehension was very limited and is still determined by geographical distance. The more diverse an area is in terms of the dialects that are spoken, the more likely it is for the different communities to understand each other.

With the development of satellite television and online media later, the four dialects, but especially Kurmanji and Sorani, spread widely. They’ve popularised the different varieties of Kurdish, and familiarised speakers with lexical and grammatical differences.

In addition, Kurds now have many more opportunities to meet, whether in Kurdistan or in the diaspora. Today there is a mobility of people that did not exist at all, or very little, in the past.

Defence, Development and Standardization of Kurdish

The defence, dissemination or efforts to standardise Kurdish vary according to the times and the states in which the Kurds live today (Iraq, Iran, Syria and Turkey).

In Iraq, despite the fierce repression of the Kurds, their language was never officially banned. So teaching, standardisation or literature, have always been more or less possible. However, the Kurds faced much discrimination and repression because of the use of their language, particularly during the Baath era.

In Turkey, Kurdish was banned, including privately and within families, from the creation of the Turkish Republic in 1923, and all works on the Kurdish language were equated with terrorism. There has therefore been a development of working groups in the diaspora. Examples include the Kurmanji Seminary or the "Vate" group for Zazaki (Dimili), which documented the language, archived songs, stories and worked on the standardisation of spelling.

It should be noted that today actors or social activists use the linguistic resources of the different dialects to meet specific needs in terms of new terms, vocabulary. For example, the Kurdish Institute of Paris has created a Franco-Kurdish dictionary with 85,000 words from the four dialects.

In recent years, Kurdish has not been formally banned in Turkey and has even been included in the education system, but as an option. But in practice inequalities are still very apparent. With all the destruction that Kurdistan has experienced throughout history, many written sources have disappeared. Despite this, Kurdish literary works of the 16th century in particular have been preserved, such as those of writers Ali Hariri, Malaye Jaziri, Faqi Tayran and Ahmad Khani.

The real development of literature in Kurdish dates back to the time of the First World War. The Kurds, realising that they have lost on the military and political terrain, are trying to save what can be saved, the language and literature that will serve to denounce their condition.

The Kurdish language, despite its diversity, still represents an essential unifying element of the identity of its people. The Kurds’ defence of their language is regarded as an existential issue for the continued survival of their culture. Despite the geographic and political schisms that continue to divide the Kurdish community both linguistically and culturally, the diversity of all of the Kurdish dialects have, over time, contributed to the richness of the global Kurdish identity.

As the media landscape in Kurdistan and around the world begins to change, the Kurdish language will undoubtedly evolve and intermix even more. Kurdish language curricula are starting to develop in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq and Turkey, making it more feasible for the next generation to learn the language and, likewise, the diasporic nature of the Kurdish people will continue to spread the language even more globally.

Special thanks to Professor Salih Akin of the University of Rouen for his assistance in writing this article, as well as Kurdish author Farzin Karim.